This Issue of the Chronicle, we present Part #6 (The Big Cities) of our 12-part series of the "History of the Sounds of Modern Music." Our objective is to follow the Sounds made by innovative Humans and their Instruments that have evolved throughout the Centuries of Man-on-Earth.

Part #1 - Early Civilizations Part #2 - Pre Civil War

Part #3 - Civil War and Post Part #4 -New Orleans Scene

Part #5 - The River Boat Era Part #6 - The Big Cities

Part #7 - The Roaring 20s Part #7 - The Swing Era

Part #8 - Post World War II Part #9 - The 1950s

Part #9 - The 1960s Part #10 - Woodstock Era

Part #11 - The 1970s Part #12 - The 1980s

The Classic Rock Chronicle

I Issue #12 July 3, 2024

Everything Classic Rock... the CRocker's Voice

The Classic Rock Chronicle was created to provide regularly updated Content about the "Goings-on" of the Vast, eclectic, and important period of Classic Rock from 1964 to 1984... Come along and enjoy the ride, Mates

Subscribers to The Chronicle can submit Topics for future Issues and Content to news@classicrockturntables.com

History of the “Sounds” of Music Part #6

The Big Cities Evolution of the Sounds of Music

By William W. Nelson

Founder of the Asheville School of Classic Rock

************

Introduction

Introductiom

In Part #6, we will cover the period from 1910 to 1920 where America was in the midst of the "Progressive Era," characterized by Social Activism and Political Reform aimed at addressing issues like Political Corruption, Workers' Rights, and Women's Suffrage.

Progressives sought to address the problems caused by rapid Industrialization, Urbanization, Immigration, and Political Corruption as well as the enormous concentration of Industrial ownership in Monopolies. Progressive reformers were alarmed by the spread of Slums, Poverty, and the Exploitation of Labor. Multiple overlapping Progressive Movements fought perceived Social, Political, and Economic ills by advancing Democracy, Scientific Methods, and Professionalism; Regulating Business, protecting the Natural Environment; and improving the Working and Living Conditions of the Urban Poor.

One of the most significant effects of Music during the Progressive Era was its use as a tool for Social Reform. The Upper-middle Class saw Music as a means of Social uplift and Amelioration, particularly for the Working Class. This belief led to the inclusion of Music Education in School Curricula, reflecting the Progressive ideals of democratic access to Culture and Education.

By introducing Music into rural Schools, the Progressive movement aimed to democratize access to Musical instruction across Social Classes... it also served as a powerful medium for expressing and promoting Social Movements. Various Reform Groups, including the Women's Suffrage movement, used Songs to build morale and spread their messages. These Protest Songs helped to galvanize support for Social causes and became an integral part of the era's activism.

The Progressive Era saw the emergence of enolving Musical styles that reflected the changing Society... Ragtime gained popularity during this period. This new Genre, with its Syncopated Rhythms and lively Tempo, mirrored the energy and dynamism of the Era. The rise of Ragtime also contributed to the evolution of jazz, which would become a defining Musical Style in the following decades.

The commercialization of American popular music also took root during the Progressive Era. The birth of Tin Pan Alley in New York City marked a new Era in the music industry... with a focus on producing and selling Sheet Music for popular Songs so Covers could be made by any Wannabee Group. This commercialization led to the creation of a new style of music that was faster and more upbeat than previous forms, reflecting the changing mood and pace of American Life. In cities like Kansas City, Music played a crucial role in shaping Urban Culture... the development of Jazz scenes in Chicago and New York provided multiple Venues for Cultural expression and Social interaction.

These Music Scenes often challenged existing Social norms, particularly around Race and Gender, even as they sometimes reinforced other stereotypes. However, it's important to note that the Progressive Era's relationship with Music was not without its contradictions. While Music was seen as a tool for Social Reform and Democratization, Racial Segregation and Discrimination remained prevalent in the Music Industry and Society at large. African American Musicians, despite their significant contributions

to American Music during this period, often faced barriers and limited opportunities. The effects of Music in the Progressive Era extended beyond entertainment.

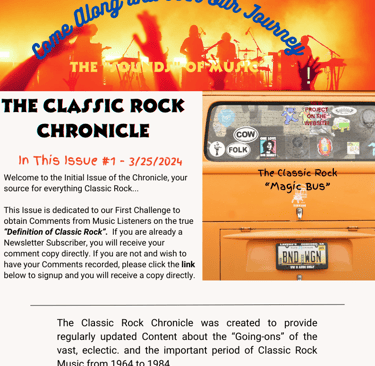

The Music Scene on the West Coast

Once the Railroads had connected Los Angeles with Kansas City and Texas by 1900, California began a major growth spurt and, by 1910, it had reached 300,000 (17th in the nation)... Spanish Folk Music and some Classical Venues were operating and featured at the Los Angeles Sympathy.

Before WWI, there was no reason for Blues Artists to test the waters there as the St. Louis Blues was not available beyond Kansas City... and African Americans were jus starting to migrate to California. Therefore, we shall see that after WWI ended things would start to change.

Kansas City

Kansas City's boom came about around 1890 as its crossroads with railroad traffic increased and a migration of African Americans came seeking freedom for life in the South. Music was mostly Folk oriented and musicians from St.Louis were heading North and East seeking their share of the upcoming rage of Blues and Jazz.

The first documented Saloon of any quality of nightlife came in 1911... a man named James A. Fitzpatrick decided to open a saloon in the Quality Hill neighborhood. It was hooked by Cable Cars and its Commercial District was ripening... making the demand for Nightlife increasing .

With the support of “Big Jim” Pendergast and his brother “Boss Tom” Pendergast, he opened Fitzpatrick’s Saloon in the building that now houses The Majestic Restaurant. The first floor featured libations while the upper floors housed a notorious brothel as well as Fitzpatrick’s residence. When Prohibition became the law of the land in 1920, the Saloon was moved to the lower floor that now serves as aJazz Club. Due to his favorable relationship with Boss Tom, Mr Fitzpatrick was able to keep a very successful speakeasy throughout prohibition. This relationship also led to Boss Tom using the top floor of the building as a secondary office for his “Business” meetings.

It would take until after the War for Musicians to make the trek from St. Louis and Chicago... and indeed it did (see part #7)

St. Louis

See Part #5 for the early Blazz Sounds...

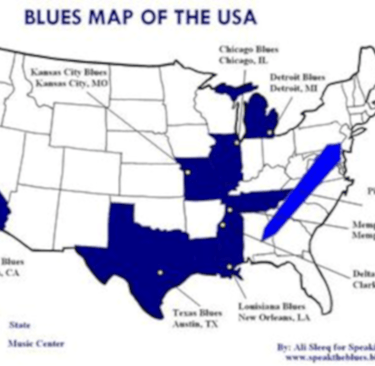

During World War I, St. Louis had an active and vibrant Music Publishing Industry that played a significant role in shaping the City's Musical Landscape. The War period saw a surge in Patriotic and War-themed Music, which was reflected in the Sheet Music produced and distributed in St. Louis at the time.

The City's Musical output during WWI was not limited to a single Genre but encompassed a variety of styles. St. Louis' unique position as a crossroads of American culture - being halfway North and South, and at the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers - contributed to its diverse Musical Influences. This geographical advantage allowed the City to blend different musical traditions, creating a rich and varied Music scene even during wartime.

Composer-Publisher Harold Dixon of the Dixon-Lane music house was

active during WWI, composing several Songs to boost support for

American Troops. Some of his notable works from 1918 include

"We're Going to Get to Berlin through the Air," "Grin, Grin, Grin," and

"You Great Big Handsome Marine".

The Patter Song for Grin-Grin-Grin describes the rationing measures

introduced by Herbert Hoover, who served as head of the U.S. Food

Administration during the war. Hoover encouraged Americans on the

homefront to avoid eating certain foods on certain days – for example,

no wheat products on Wednesdays.

Midtown was open during WWI but many Saloons closed due to a lack of attendance... After the war, in May 1919, St. Louis hosted a large homecoming celebration for returning troops. But, things came alive when Prohibition began in January 1920 when all of the closed bars became "Speakeasies" (see Part #7)

Chicago

World War I led to increased industrial production in Chicago. Previously closed industrial jobs became available to African Americans due to labor shortages caused by the war. There was a major influx of African Americans from the South, with at least 50,000 black Southerners moving to Chicago between 1916 and 1920. This period is often referred to as part of the "Great Migration"

Unlike St. Louis and Kansas City, Chicago Nightlife actually became more lively than before the War... mainly due to the Industrial expansion and the need for Workers (anyone who wanted a job... had it!). Everyone had enough income to have some to spare for entertainment and there was no lack of it for anyone who wanted it.

After trickling into the American vocabulary over the previous couple of years, the word Jazz burst into common use in 1917. On January 19, an advertisement by the Boston Store, a department store in Chicago’s Loop, defined Jazz as “the droll Saxophone Music has been so successfully imitated by the Piano.” The ad was promoting player Piano Rolls for sale for the songs “Allah’s Holiday,” “Bachelor Days,” “Florida Blues,” “Chicken Walk,” and “If You Ever Get Lonely.”

************

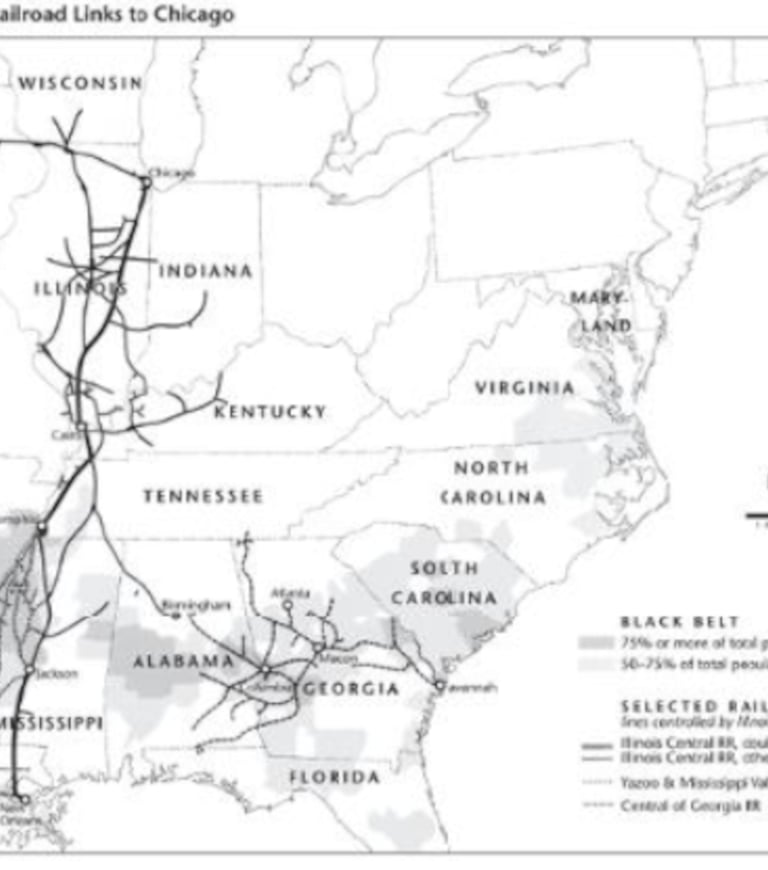

Before widespread automobile ownership, migration from the South generally followed water and rail routes. Chicago's popularity as a destination rested in part on the breadth of the Illinois Central Railroad network.

By the time World War I opened employment opportunities for African Americans in northern cities, the Illinois Central and its feeder lines had penetrated many of the plantation regions where black population was most concentrated. Other railroad lines also offered access to Chicago from these and other parts of the South. Until 1916, black Chicagoans were likely to have roots in the upper South.

Beginning in 1916, Chicago drew its African American population from the Deep South, especially Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, and western Georgia.

Fundamentally, perhaps, [Jazz] is the expression of his savagery; the hysteria, the madness that underlies all his life; the loudness of his laughter, the brutality of his rage, the bestiality of his lust; the plaintiveness and childishness of his sorry.

Technically, it is the tom-tom of his Meter, the sob of his Cello, the wail of his Violin, the moan of his Trombone, the dying-cur-in-its-agony of his Clarinet. It is the sinister, the elemental, the “blue” of the African Soul. If realism be art, the Jazz of the Negro is art of the first water.

The White Man has seized upon this quality and made it his own. He has taken it to his vilest Bordellos; he has exploited it in the Temple of the hyper-moron—vaudeville; it is “the rage!"

The Youngstown Telegram offered this description of Jazz:

"Usually, the Jazz Band is made of a Pianist who can jump up and down while he is playing; a Saxophone Player who can stand on his ear; a Drummer whose right hand never knows what his left hand is doing; a Banjo Plunker; and a Violinist who can dance the Bearcat.

While the music is throbbing and the Dancers are swaying, they get into action until the air is full of flying feet, grabbing hands, drummers’ gimcracks, and delighted exclamations. The exclamations are usually such as “Attaboy!” “Oh, doctor!” “Swing me dizzy!” and “Oh, Babe!”"

Robert W. Stevens, the University of Chicago’s Musical Director, came to the defense of Jazz, noting that Wagner, Brahms, and Liszt had all composed Music with similarities to Jazz.

“As for Brahms, his ‘Hungarian Dance’ in F sharp minor is in principle the same thing that we condemn in the Ragtime of a Jazz Band,” he said, also pointing to Liszt’s Second Rhapsody as a composition that included “some more nice Ragtime.”

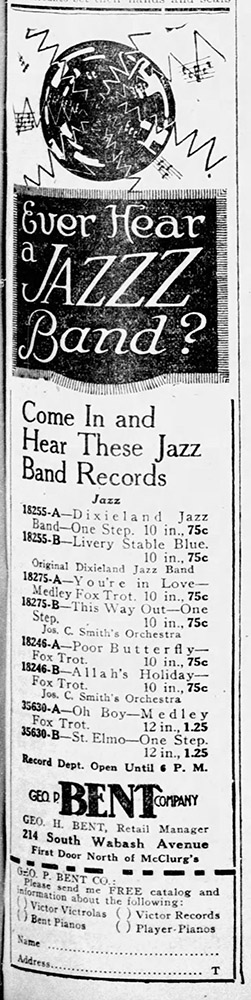

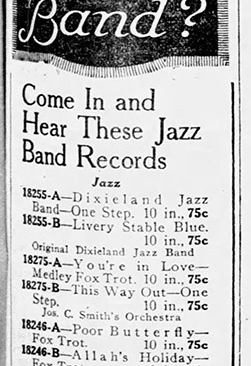

The Geo. P. Bent Company, 214 South Wabash Avenue, enticed shoppers with an advertisement asking: “Ever Hear a JAZZZ Band? Come In and Hear These Jazz Band records.”

The Chicago Daily News wrote about a Woman who borrowed someone’s Record of a “Syncopated Jazz Band Rag” and played it until it was worn thin, breaking into seven pieces.

And Dance Instructors began offering lessons on how to Dance to Jazz music, as the Tribune reported: “The Super-Jazz has been newly created, devised, invented, constructed, or what-you-may-call it, by Arthur L. Kretlow of 637 Webster Avenue. Prof. Kretlow will present the Super-Jazz for the Chicago Association of Dancing Masters’ Normal school.”

It became trendy to do jazzy versions of old Songs. For example, the Steger Talking Machine Shop at Wabash and Jackson advertised Arthur Collins’s record “Get a Jazz Band to Jazz the Yankee Doodle Tune.”

But the Daily News jokingly complained that this fad could go too far: “Putting jazz in the wedding march may be all right, but a neighbor of ours is trying to jazz ‘Hark, from the Tomb’ and the ‘Dead March.’ Suggests that the hearse chauffeur might be arrested for exceeding the speed limit.”

As that comment suggests, fast tempos were a key part of early Jazz Music.

Newspapers sometimes described Jazz as a noisy, tuneless Racket, questioning how anyone could enjoy it.

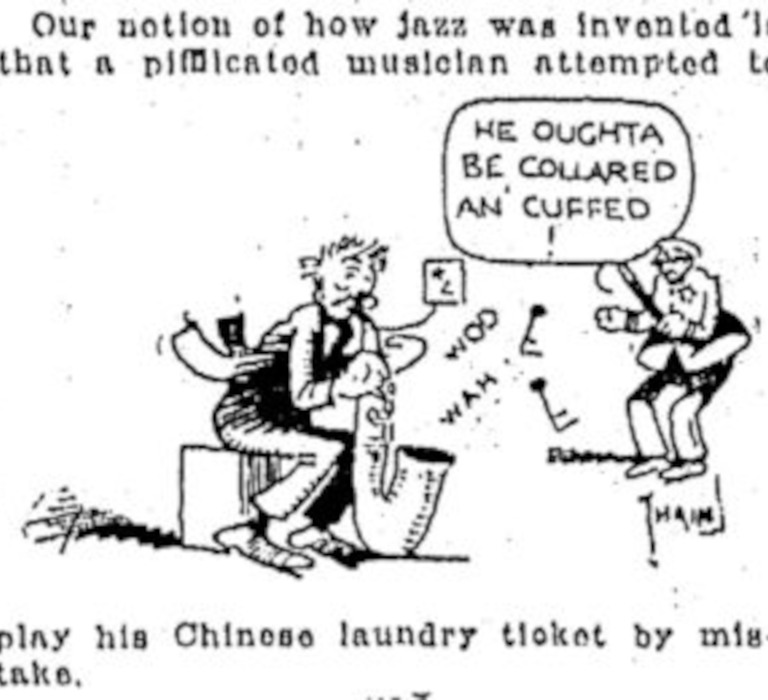

“Our notion of how Jazz was invented is that a pifficated Musician attempted to play his Chinese laundry ticket by mistake,” the Daily News commented, illustrating the joke with a cartoon.

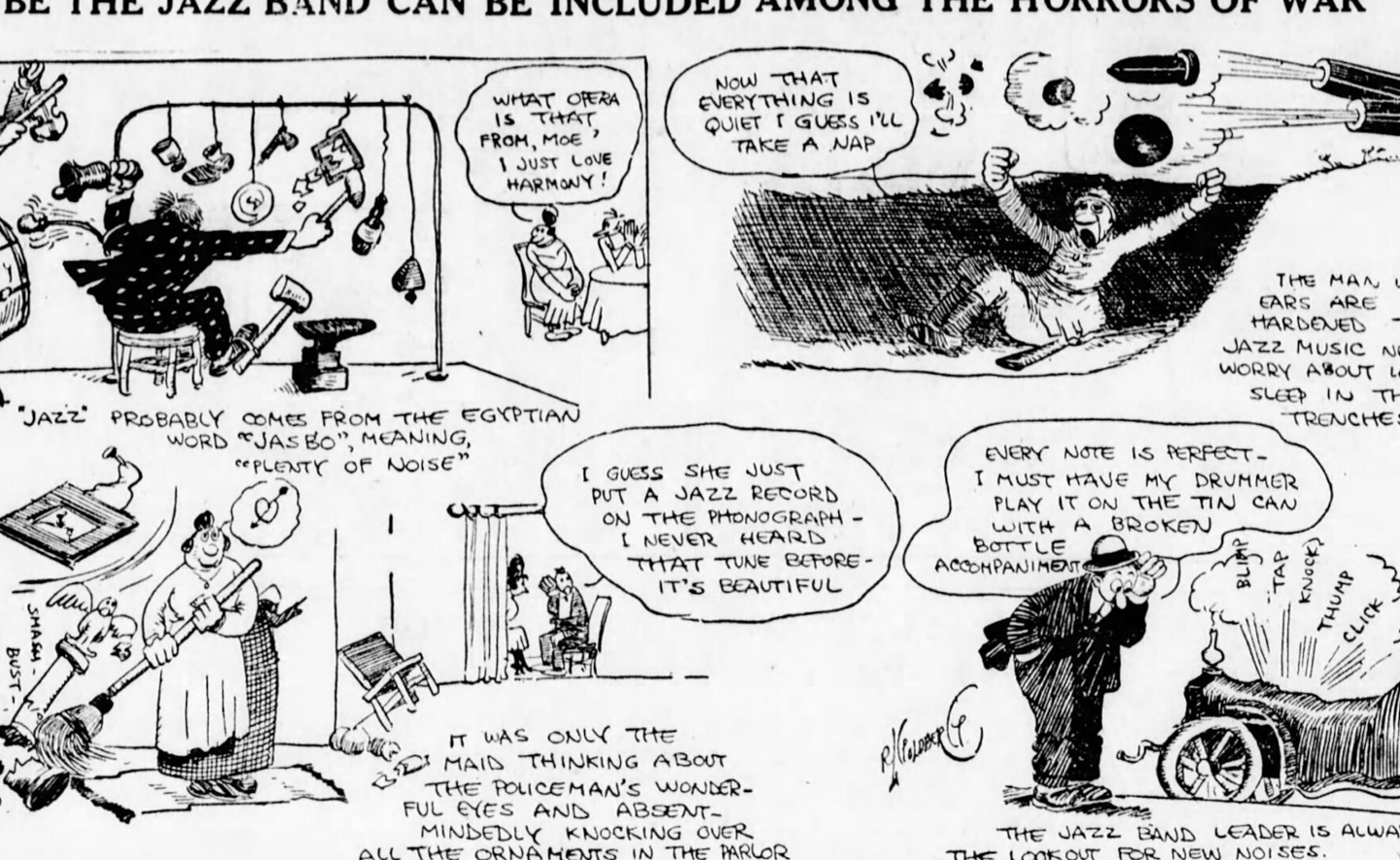

A syndicated comic strip by Rube Goldberg, which appeared in the Daily News on September 21, 1917, included a humorous stab at the word’s etymology:

“‘Jazz’ probably comes from the Egyptian word “jasbo,” meaning “plenty of noise,” a caption said.

Chicago Daily News, October 16, 1917

Alluding to Men who were headed to Europe to fight in trenches, the Comic also said, “The man whose Ears are hardened to Jazz Music needn’t worry about losing sleep in the trenches.”

The Comic Strip also showed a Man looking at car making noises: blurp, tap, knock, thump, click. “The Jazz Bandleader is always on the lookout for new noises,” it explained. This Bandleader exclaimed: “Every Note is perfect—I must have my Drummer play it on the Tin Can with a Broken Bottle accompaniment.”

Writing in the Daily News, critic John V.A. Weaver Jr. argued that Jazz was “the essence” of African American Music. Although he seemed to be expressing some appreciation for Black jazz—while criticizing the versions of the Music performed by white Vaudeville Artists—Weaver revealed his notions about what “the essence” of Black People was:

World War I and Alcohol

As the United States started sending American Soldiers to fight in Europe, the Campaign against Alcohol was ratcheting up. It became a crime to sell Alcohol to Soldiers. Liquor sales were forbidden within five miles of any Naval Base.15 And for Americans who hoped to preserve their right to drink Beer, it didn’t help that most of the country’s Brewers were of German heritage.

“We have German enemies across the water,” a dry politician in Milwaukee remarked. “We have German enemies in this country too. And the worst of all our German enemies, the most treacherous, the most menacing, are Pabst, Schlitz, Blatz, and Miller.

Turmoil grew as there was no real official attempt to control the Alcohol issues until... as 1917 came to a close, and the National Campaign to prohibit Alcohol reached a major milestone. On December 17, the U.S. House of Representatives voted 282 to 128 to send a constitutional amendment to the states.

(Source)

To be continued in Part #7

New York City

New York became the home of the Metropolitan Opera House in 1882 and Carnegie Hall in 1891, the latter's opening being marked by an appearance by the famed Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. In 1892, Antonín Dvořák became Director of the National Conservatory of Music. Dvořák, a Bohemian composer, was fascinated with Native and African American folk music, and he was enthusiastic about encouraging a nationalist American field of music that utilized those fields.

The first New Orleans Jazz Bands to perform in New York arrived as Vaudeville Acts, sharing the lineup with Jugglers, Comedians, and other traveling Entertainers. Northeast Vaudeville audiences hardly expected a Jazz Revolution in their midst, and few had any sense that Music history was being made on Stage.

When legendary Cornetist Freddie Keppard brought his version of New Orleans jazz to New York’s Winter Garden in 1915, the New York Clipper reviewer praised the band solely for its “comedy effect” and ignored the music while lavishing attention on the accompanying dance of an “old darkey” who “did pound those boards until the kinks in his knees reminded him of his age.” When the band returned in 1917, press coverage was even less enthusiastic; one reviewer denounced “a noise that some persons called ‘music’ ” and insisted that the musicians were “each vying with the other in an effort to produce discord.”

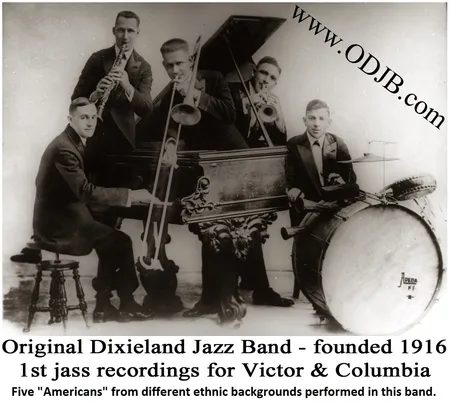

The Original Dixieland Jazz Band, a group of New Orleans Musicians,

got a better reception in New York that year. Columbia Records,

hoping to take advantage of the group’s successful engagement at

Reisenweber’s Cafe in Manhattan, invited the musicians to its

Woolworth Building studio on January 31, 1917. But the label execs

decided that the ensemble’s strange, loud music was too noisy to

record. They dismissed the players before the day was done, and

no records were issued. Four weeks later, the Victor label succeeded

in recording the band in its New York studio, and the resulting tracks

—the first Jazz Records ever—were instant hits, eventually selling

more than 1 million copies.

Here at the dawn of Jazz recordings, New York could have outpaced the competition and taken the lead. But the Original Dixieland Jazz Band soon left New York to enjoy a long residency in Europe. New York Record Labels might have seized the opportunity by signing the leading African-American musicians from the South, but for a variety of reasons, they didn’t.

When W. C. Handy, then living in Memphis, was invited to bring a 12-piece Band to New York to record for Columbia, he could find only four Musicians willing to make the trip. He traveled to Chicago to fill the remaining spots, but encountered hesitancy and suspicion there, too. “Like Memphians, Chicago musicians had never heard of a Black Band traveling to and from New York to make Records,” he later recalled. When Freddie Keppard had a chance to make the first Jazz Recordings for Victor in 1916, he also expressed reservations, but for a different reason. “Nothin’ doin’ boys,” he told his bandmates. “We won’t put our stuff on records for everybody to steal.”

Meanwhile, Jazz was taking Chicago by storm. The greatest talents in New Orleans Jazz set up shop in the Windy City during the years following World War I. Sidney Bechet moved to Chicago in 1917. Jelly Roll Morton had visited Chicago in 1914 and would later return for a long stay—the City served as his home base when he made his most important recordings in the 1920s. King Oliver first found widespread acclaim as a Chicago Bandleader during that same period, and Louis Armstrong first came to public attention as a member of Oliver’s ensemble, while it was performing in Chicago.

Why did Jazz ever leave New Orleans? Today, the "Big Easy" still tries to build Tourism claims around its jazz Heritage, but all the boasting and brochures can’t hide the fact that New Orleans’ Jazz scene has been declining. In 1918, Columbia Records tried to seize the momentum of the first Jazz records by sending talent scout Ralph Peer to search for recording acts, but Peer shocked the home office with his telegram after three weeks on the job: “No Jazz Bands in New Orleans.” (just Blues)

The usual reason given for the departure of the first generation of New Orleans talent is the closure of the City’s Red-light district in 1917. Without Brothels, the story goes, Jazz Musicians had no place to play. The real history is more complex. True, many Musicians lost gigs as a result of the Navy’s determination to clean up New Orleans, but other factors contributed to this exodus, from the influenza epidemic that ravaged the City to sheer wanderlust.

But the biggest reason Jazz Musicians had for moving to Chicago was the simple desire to escape the institutionalized Racism of the South and find better economic opportunities. A half-million African-Americans eventually relocated from Southern states to Chicago... musicians, along with everyone else.

A colorful tale is often told about Jazz Musicians moving into the Midwest via Mississippi River Steamboats. In fact, this migration mostly took place via Railroads, and Scholars have shown that a Black Southerner’s likelihood of migrating North could be predicted based on the proximity of a Railroad Station to the person’s place of birth. Many made their relocation decisions depending on which major City lay at the end of the line. The "Great Migration" changed the Musical history of America, with blacks from Louisiana and Mississippi—along with their Jazz and Blues traditions—often settling in Chicago, while those from Virginia, Georgia, and the Carolinas frequently headed for New York.

(Source)

To be continued in Part #7

Philadelphia and Boston

The Blues and Jazz had not caught on yet in Philadelphia and Boston... but, as we shall see, the Roaring 20s did leave its mark there... to be contained in Part #7

In Part #7, we will cover the "Roaring Twenties" period before the "Great Depression" in 1929... it was a period of economic prosperity with a distinctive cultural edge in the United States and Europe that would influence People's tastes in music and fashion... including the introduction of Swing Jazz.

The Social and Cultural features known as the Roaring Twenties began in leading Metropolitan Centers and spread widely in the aftermath of World War I. Its spirit was marked by a general feeling of novelty associated with modernity and a break with tradition, through modern technology such as Automobiles, Moving Pictures, and Radio, bringing "modernity" to a large part of the Masses.

Formal decorative frills were shed in favor of practicality in both daily life and architecture. At the same time, Jazz and Dancing rose in popularity, in opposition to the mood of World War I. As such, the period often is referred to as the Jazz Age.

© ClassicRockTurntables.com

All Rights Reserved